Recently, I attended an Adelaide University event called Research Tuesdays, where one receives a free ‘crash course’ of sorts, with the university promoting their recent research projects. The hour-long session was called “Animals in Society – from fork to friend”. It basically was a brief consideration of research being undertaken regarding many facets of animals. The professor running the topic was Gail Anderson, from the school of veterinary science.

She explained how research on animals has taken place mostly concerning the human benefits involved. Production animals (such as cattle, pig, alpacas, etc) have a financial appeal to people. Animals have also been useful as models for human disease, and studying therapies for those diseases. Research concerning wild animals often has an overarching environmental aim. There was also a mention of animals used in ‘recreation’, such as racing animals. Finally, the category of companion animals was considered, and that this was an expanding field as there are ongoing discoveries regarding the human-animal bond.

I will briefly summarise the other categories before considering the companion animals in more detail.

Firstly, production animals need to be as profitable as possible – so research is ongoing into the best way to increase profits from animals. Additionally, there is increasing concern regarding animal welfare and sustainability of practices. All of these are research pressures in the production animal industry.

Animal welfare allows for the use of animals in experimental conditions, such as testing human treatments. There are obviously ethical issues concerned, and there is concern from animal rights groups, as well.

Research into wildlife seeks to maintain environmental populations, discover “extraordinary metabolic pathways”, and otherwise use animals (such as frogs) as environmental indicators. Emerging diseases may also be found in wildlife.

Recreational animal research is often centred around welfare, but also ‘increasing speed’ (and so financial gain). In terms of dogs, there are studies being commenced that attempt to measure heat stress, and its implications, on racing groups. Particular, methods of ‘cooling’ after racing will be considered. The ultimate aim of this research is to establish welfare protocols – so potentially establish a ‘too hot to race’ policy, and a universally effective method for cooling animals down.

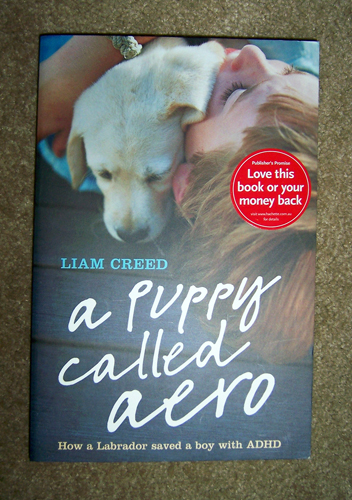

Companion animals, admittedly, were a small segment of the talk. Anderson explained how 63% of Australian households (and 62% of USA households) have pets. As many pet owners place their animal’s health before their own, and prefer their pet’s company to people, then this poses ‘risks’ to people that risk their own well being for the sake of their pet.

We also need to consider the therapeutic value of companion animals – with proven studies shown that touching animals reduces blood pressure, and that caring for animals empowers people. There was also mention made to the fact that there is a strong relationship between harm to animals and harm to children. (That is, if a vet sees animals being harmed in a household with children, serious consideration should be given to the wellbeing of those children.)

Companion animal treatments are becoming increasingly specialised. Vets are becoming specialists in fields or in particular animal species. Animals that are of particular benefit to people, such as guide dogs, are privy to methods to determine hip dysplasia and arthritis earlier, prevent its onset, and also prevent its occurrence by genetic screening.

This is a brief overview of what was overall a brief session, but I hope it is of a small interest to those involved in animals in some way.

(On a side note, question time revealed that cortisol levels are reflective of stress, but that handling of animals in order to obtain samples can increase the stress of animals and so also cortisol levels. This has implications for the changes seen in Belyaev’s fox experiment, as the difference between the domesticated and undomesticated foxes could have been exaggerated due to undomesticated foxes being more stressed from handling, and so revealing a higher cortisol level.)