Dog Anatomy in Pictures

Dog Anatomy graphic created by Matt Beswick for Pet365. Click here to view the full post.

Dog Anatomy graphic created by Matt Beswick for Pet365. Click here to view the full post.

A increasingly common rhetoric in the rescue community goes along the lines of, “I’m not against breeding, just breeding when the pounds are full” coming along with the suggestion “just stop breeding for a few years, until the pounds are empty”.

This is a misguided suggestion. While this almost sounds good to the uneducated ear, it seems to imply that the dogs in pounds are exactly the type in demand or that there is a dog in a pound to suit every person. Further, ceasing breeding for 3 years would have an impact on not just breeders, but breeds as a whole, on any organisation with working dogs (guide dogs, custom dogs, farm dogs). Also, placing a ban on breeding is just unenforceable. However, the biggest issue with this suggestion is that it doesn’t target the source of the problem. I’ll look at all these issues in more detail.

Pound dogs aren’t for everyone

The dogs available for adoption in pounds is not highly varied. The suggestion that ‘anyone’ can find the dog that is perfect to their household is erroneous. There’s simply not a large variety of dogs in pounds to suit the demand. The reason that breeders (good and bad) are popular is they fulfil a demand that is not met by pounds. Small white fluffies, and indeed small dogs overall, are not well represented in the pound system.

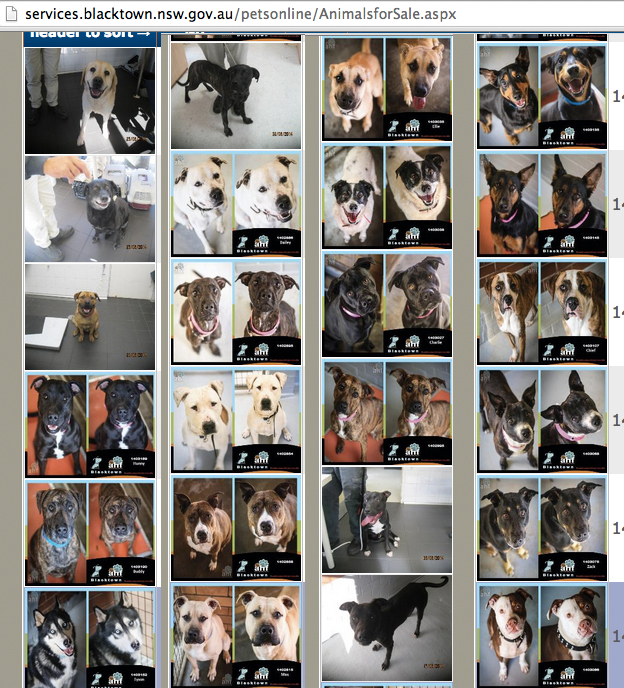

I looked at the first page of dogs available for adoption at Blacktown Pound (NSW). You can see that most dogs are working or bull breed type, and most are medium to large in size. Not a great deal of variety.

Some might argue that if someone really needs or wants a particular type of dog, they should just wait for it to end up in rescue. Is it really fair for someone to wait 2 year or more for a dog that may never appear in rescue? Personally, I was waiting 18 months looking for a dog in rescue (with the requirements that the dog be big, with a wire coat, and very good with other dogs). I gave up waiting and went to a breeder. I feel like I was more than patient, but a dog suiting my needs just wasn’t available to me in this period of time.

On the same date, these are the available pets at Broken Hill Pound NSW available on the 26th of June. Again, the dogs are mostly medium-large working or bull breed types

The other alternative is that people may just get the dog that is available instead of the dog right for them. Did you know that at least two studies (see: one / two) found that 22.5% of the dogs relinquished to a shelter came from a shelter to start with? Being from a shelter is a risk factor for relinquishment in itself, and proposals that people should ‘have to’ acquire a dog from a pound actually seems circular to the end goal of clearing shelters of pets.

Implications for Working Dogs

Seemingly in Australia, about 700 dogs are bred for customs and guide dog work each year. These professions have targeted breeding programs to select for characteristics important for that dog’s individual role. They’ve obviously done the maths, and figure that it’s more cost effective for them to breed their own dogs than take dogs out of shelters and pounds. The proposal that breeders should ‘just stop breeding’ until pounds are empty means that either these programs suffer financially, or the community suffers by not having any dogs at all for several years or more (or forever, really).

Another industry that would suffer would be dogs used on properties for herding or as livestock guardians. These agricultural branches have specially bred dogs for their purposes. Many farms find the work of dogs invaluable, and would also be financially impacted by a breeding ban.

Enforcement is not going to happen

I’ve blogged at length about all the types of legislation that continually goes unenforced Australia-wide, yet touted as ‘good’. In reality, animal legislation is horrendously unenforced. If microchipping laws get flaunted, breeder licensing flops, and the animal welfare acts regularly are violated nation wide, what hope do we have of ceasing dog breeding for a particular period of time?

Dog and Breed Welfare

The idea that breeding should just stop for ‘a few years’ neglects to mention that ‘a few years’ is a long time in a life of a dog.

Let’s say you have a breed that lives until about 12 years old. Three years is a quarter of that dog’s life. That means the dog is middle-aged by the time it is 6 years old.

What I’m getting at is that if you were to ban breeding for a few years, we are going to be breeding older bitches, which we know is riskier. (As bitches age, they have smaller sized litters with bigger individual puppies, which is riskier for the bitch to whelp.)

This means that, for the individual bitches involved, this is bad for their health.

On a broader scope, if breeders choose not to breed their bitches because of a breeding ban, this could put the health of entire breeds in jeopardy. If a bitch is especially important (maybe she has hip scores of 0/0 in a breed with a high incidence of hip dysplasia, or maybe the bitch was imported from Sweden and is important for improving genetic diversity within the breed in Australia), then the loss of this bitch’s progeny to the breed is significant.

Basically, a breeding ban is bad for individual bitches, as they will be bred older, to their detriment. And a breeding ban is bad for breeds, as desirable or important bitches will not be able to make substantial positive impacts on their breed.

Is this really where we should focus?

My biggest gripe with this is it is, again, taking the focus away from the pound – the place where killing happens.

Pounds have an obligation to promote and market their animals. Let’s ban pounds from killing and so obligate them to make changes to their approach!

The other gripe is that this proposal works on the basis that there is an overpopulation program – there isn’t an overpopulation problem.

And: pounds will never be empty! Pounds have an important community service reuniting pets to their families. If my dogs got lost, they’d probably end up in the pound (if not scanned for a chip prior), and I’d be grateful for that.

A ban on breeding, even for a short period, is not a solution to shelter killing.

The ‘Week in Tweets’ is name in the optimism that I will post a Twitter round up on a weekly basis. This sometimes happens, and sometimes it doesn’t. But here’s everything we’ve tweeted about for the last few weeks. It’s basically my ‘recommended reading’ list.

Phoebe – one of the current rescue dogs available for adoption. Find out more about Phoebe.

Tweet of the Week

It’s tax time! So PetRescue is running their annual campaign to encourage tax-deductable donations. PetRescue is a great resource for Australian rescues. Read more: The lives of more rescue pets are depending on us.

Domestication, Breeds and Breeding

The Wolf in the Dog House and How Accurate are Dog Breed DNA Tests? from Terrierman.

The Hierarchy of Border Collie Smugness from Border-Wars.

Genomes of modern dogs and wolves provide new insights on domestication.

Dog Science

How your dog protects you from getting allergic.

Aggressive behaviour in dogs: a survey of UK dog owners.

Do dogs with baby expressions get adopted sooner, and what does it say about domestication?, Do children benefit from animals in the classroom? and The Posts of the Year 2013 from Companion Animal Psychology.

Under pressure: Harness for guide dogs must suit both dog, owner.

Rescue, Sheltering and Welfare

Compulsory cat registration in QLD – an expensive flop. and Business as usual. from Saving Pets.

Beloved dog killed three days before letter from council.

Garland Country, AR struggles with the after effects of breed specific law.

Rescuing Riley, puppy rescued from 350′ deep slot canyon.

Lindsay’s Column: What does ‘no kill’ really mean?

Training and Behaviour

The Problem of Self-Reinforcing Behavior from Terrierman.

Dog training: Ways to use hand targeting.

22 rear end awareness exercises for dogs (video).

Epic recall failure from Denise Fenzi.

The Dog Whisperer is No Longer Relevant.

Is lip licking beagle a threat to baby?

Other Animal Stuff

Border Terriers on My Instagram

Other Dogs of My Instagram

Bailee takes herself into her crate to sleep, after chasey with Landy.

![]() While reading up on CECS in border terriers, I happened upon a condition called ‘Scottie Cramp’. I was keen to learn more, and found the article “Hyperkinetic episodes in Scottish Terrier dogs” (and, more importantly, the reproduction of its text on the Scottish Terrier Club of America website).

While reading up on CECS in border terriers, I happened upon a condition called ‘Scottie Cramp’. I was keen to learn more, and found the article “Hyperkinetic episodes in Scottish Terrier dogs” (and, more importantly, the reproduction of its text on the Scottish Terrier Club of America website).

Scottish terriers. Photo courtesy of Argowan Scottish Terriers. (Photo for illustration purposes – these dogs do NOT have scottie cramp.)

What is ‘Scottie Cramp?’

‘Scottie Cramp’ is the popular term for hyperkinetic episodes in scottish terriers. This is a central nervous system problem that causes the hindlegs of effected Scottish Terriers to ‘cramp up’ so they kind of ‘skip’ with their hindquarters.

This condition is often brought on by excitement or exercise, and gets worse as exercise progresses. Generally a walk of 90m-600m was enough to bring about symptoms in affected dogs in this study. (However, there was one badly effected dogs who displayed symptoms after 10m.)

Usually a dog will exhibit symptoms before 18 months of age, and this condition does not seem to affect the dog’s lifespan.

What does it look like?

The paper does a pretty good job of describing this disorder. So here’s what they say with some added emphasis from me:

During exercise, the onset of a hyperkinetic episode was usually indicated by a slight abduction of the front legs, resulting in an arclike motion of the limbs while extending. The back then became arched in the lumbar region, and the hind legs were quickly overflexed and then swiftly returned to the ground. This motion has been appropriately described as a “stringhalt” gait.

The front legs became increasingly stiff, and while walking were quickly extended then flexed. In rare cases where the back was not arched, the dog walked with a “goose step” gait. Forward movement was usually hindered, and in severe cases was completely absent, resulting in the dog walking in place. Facial muscles did not appear to be affected at this time…

Occasionally, when the younger dogs were running, the hindquarters would suddenly and strongly become elevated, often to such a degree that the dog somersaulted. If the inducing stimulus was continued, the hind legs became increasingly resistant to flexion, which finally resulted in a pillarlike stance, with the dog unable to walk. If the dog fell down, it would curl into a ball with its head, limbs, and tail tucked in; breathing would appear to cease. The severe seizure would last approximately 15 seconds, after which the dog appeared relaxed and panting. During or just preceding a severe episode, the facial muscles were often affected, and the dog was unable to open its jaws.

None of the dogs lost consciousness during an episode, nor did they appear to be in pain. A short period of rest would alleviate the hyperkinetic episode in most dogs, but the signs would quickly reappear if the inducing factors were not eliminated.

Here’s a video showing a scottie with this cramping disorder, and a ‘normal’ scottie:

What causes it?

This was a small study of only 10 dogs, but the results seem to indicate: “Excitement and fear facilitated the hyperkinetic episodes, whereas anxiety and apprehension were often inhibitory”. (Personally, I am not sure that fear and anxiety are different enough to form this kind of conclusion.)

They also found that amphetamine sulfate, when injected intramuscularly, caused symptoms within 15 minutes.

There was a lot of variation between dogs and symptoms, but it seemed that frequent exposure to the trigger, the dogs tended to build tolerance. However, no dog ‘recovered’ (i.e. ceased to display symptoms).

What fixes it?

As this is a Central Nervous System problem, drugs that target the CNS, naturally, are effective.

Symptoms can be alleviated by some drugs (such as chlorpromazine, acepromazine, and diazepam) injected intramuscularly. In the case of chlorpromazine, injection intramuscularly during a seizure caused cessation of symptoms within 15 minutes.

Diazepam worked to stop dogs seizing, and also to prevent seizures (given twice daily to affected dogs).

While Vitamin E has been anecdotally suggested as a preventative, this study did not find it to be effective.

How is Scottie Cramp diagnosed?

3 criteria for scottie cramp:

1) abnormal gait or seizures during excitement,

2) injected amphetamine should induce an episode, and

3) administering diazepam or promazine during a seizure should cause prompt remission.

Reference:

Meyers KM, Lund JE, Padgett G, & Dickson WM (1969). Hyperkinetic episodes in Scottish Terrier dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 155 (2), 129-33 PMID: 5816228