In January, I blogged about the Select Committee on Companion Animal Welfare, including my submission to the committee. Recently, the committee has published their report, in which my submission is listed number 118 (out of a total of 168 submissions).

You can download the full 64 page document from the Parliament SA site.

To say I am disappointed in the Select Committee’s findings would be an understatement. When the submission processed asked writers to provide evidence for their recommendations (i.e. “The information you provide as evidence should be factual and capable of being substantiated.”), I was anticipating a research-based report from the committee.

Sadly, a evidence-based-approach was only required from the writers, and not by the committee itself.

They don’t even keep this government ‘public opinion’ approach a secret, saying:

Companion Animal Issues have become more prevalent in recent years, with most states and territories amending existing legislation and regulations or creating new ones that reflect the concerns shown within the greater community towards the health and welfare of their beloved pets.

That is, the Select Committee acknowledge legislation and regulation change based on ‘public concern’ instead of evidence of that legislation or regulation making improvements or fixing problems.

Well, that’s a flawed approach, isn’t it? Shouldn’t it based on science and evidence that show methods for improving health and welfare? Why would be just do what the public wants when it may not actually see the improvements that we seek?

They committee has made a number of recommendations that are problematic. I will begin to dissect them here.

The Issues with Microchipping

The Select Committee praises Victorian and Tasmanian legislation, where dogs must be microchipped in order to be registered. They also praise NSW legislation where animals must be microchipped before sale and before 12 weeks. The rationale is that such legislation would see more pets reunited with their owners if they become lost.

However, they provide no evidence that this legislation is effective at improving animal welfare. The only evidence produced by the Select Committee regarding this Victorian legislation was the support from the RSPCA and the Victorian government. That’s not evidence, guys. That’s spin.

While I support microchipping and to an extent this law, enforcement is hugely lacking. In NSW, just look at Broken Hill Pound or Tamworth Regional Pound or Renbury Farm to see the number of dogs that get impounded into shelters without microchips, despite it being mandatory in the state. How are so many litters being sold or transferred unchipped? Where is the policing?

The Committee wants all dogs and cats to be microchipped in the hopes that lost pets can return home more readily. However, they neglect to specify the requirements that shelters, pounds, and vets would have regarding microchpping and identifying pets as they come in. Currently, there is no legal obligation for any individual to check a microchip on animal impoundment. This is a huge flaw in state legislation and it needs to be addressed.

The Issues of Breeder Licensing

All the legislation I’ve been criticising on this blog seems to be praised by the Select Committee. They like Victorian legislation (where a certain number of entire dogs requires an individual to be registered as a ‘business’), but I have critiqued the new proposed legislation here, and for it’s lack of evidence here. The Select Committee seems to praise the findings made by the NSW Companion Animal Task Force, which I have already criticised here. The Committee also looked at the Gold Coast scheme, which I have criticised as “Clean and Kennelled“.

The basic recurrent theme in all this is it provides little lee-way for people to raise puppies in home environments, only in disinfected kennel blocks. This is detrimental to dog welfare.

The rationale behind breeder licensing is that if breeders are licensed, then codes of conduct legislation concerning animal welfare can be upheld. The Committee wants a code like the NSW one in SA. The Select Committee says such legislation “Will ensure a better and enforceable welfare standard for breeding companion animals.” However, while it may provide an enforceable standard, that doesn’t make it better than the current standard (Animal Welfare Act) that applies to all animals (not just breeding animals). Furthermore, having an enforceable standard doesn’t mean it will be enforced.

It fails to realise that individuals who are ‘puppy farms’ already fail to comply to the Animal Welfare Act, and so are unlikely to sign up to a breeder scheme. I’d pay money to see the puppy farmer that says, “Well, I’ve been neglecting my responsibilities under the Animal Welfare Act for years, but now that this breeder scheme has come in, I guess I better sign up.”

The RSPCA admits that puppy farms are hard to police because animals are often kept inside sheds. How is breeder licensing going to fix this? The Select Committee thinks such legislation will mean consumers can be more confident in their purchases. Again, only if it’s enforced… And the RSPCA already said it’s too hard to know where puppy farms are… So sorry, how? Isn’t it better to just recommend that anyone purchasing a puppy visit the home/environment the puppy is raised and use their own discretion?

The Select Committee describes how the RSPCA supports a breeder licensing scheme. Well, of course they do, it deflects public attention away from their own failings. There’s probably financial perks in it for them, too (as undoubtedly they would be enforcing such legislation).

The Select Committee quotes how the D&CMB supports a breeder licensing scheme. Well, of course they do, they’re really into desexing, and a breeder licensing scheme is a means to get more of that. There’s probably a little bit of financial incentives there, too. (Dog registration profits have to partially go to the D&CMB, so why wouldn’t the breeder registrations go there, too?)

Of the bodies quoted, the AWL is the only one that seemed to indicate that they understand where puppies come from (i.e. backyard breeders). Unfortunately, the Committee doesn’t heed this, and instead makes an incredibly heinous suggestion:

The committee recommends the scheme contemplate the inclusion of provisions for temporary licences to cover owners whose animals incidentally become pregnant, or who wish to breed one time only, and consider a sliding scale of fees to reflect the varying scale of breeding operations.

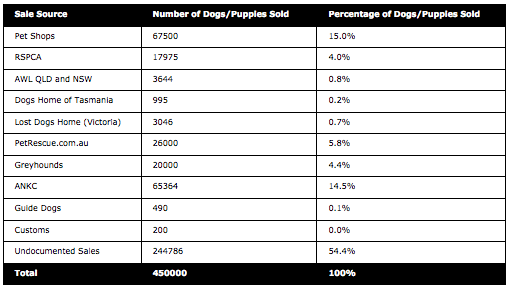

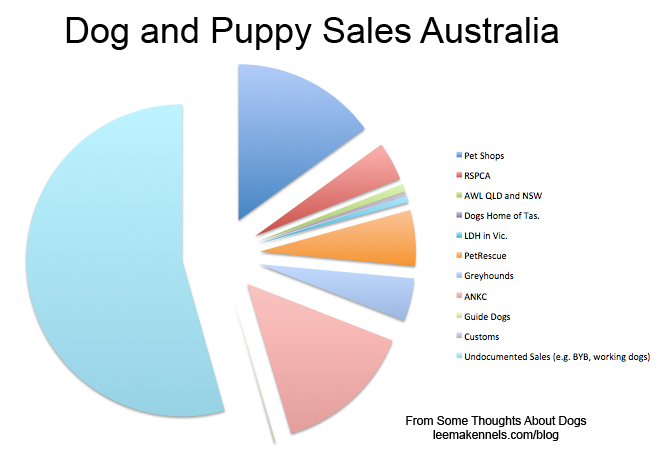

That is, if you’re a backyard breeder, you can get a temporary license and all is dandy. Sorry, I’ll link it again: Puppies come from backyard breedeers.

The Committee also suggest that working dogs would be exempt from a breeding license scheme. I am confused as to how working dogs should not be raised in ethical ways. I also assume that greyhounds may also be exempt from this legislation.

So, in summary, the Committee believes that a breeder licensing scheme “Will enable proper identification of breeders and should discourage disreputable breeders.” How will having a licesnsing scheme discourage disreputable breeders? Firstly, if breeders are being disreptuable, what about the new legislation will cause them to become reputable? Secondly, if puppy farms are hiding in sheds, how will new legislation discourage them from continuing to hide puppies in sheds? Thirdly, reputable breeders rarely make money from breeding, and if their finances are already tight, isn’t it conceivable that that reputable breeders will also be discouraged from breeding?

Apparently, that’s not an issue for this Committee. Susan Close made it clear that the recommendations in the report were “aimed at decreasing the number of dogs and cats being born”. That is, it seems the Committee had an ulterior motive: This report isn’t about improving companion animal welfare, its about decreasing companion animal breeding. In this light, all the recommendations made make sense.

Enforcement is Lacking of the Animal Welfare Act

The Select Committee are proposing changes to The Animal Welfare Act, The SA Code of Practice For the Care and Management of Animals in Pet Trade, and The Dog and Cat Management Act.

But, if they want to make sure that that cruel practices do not continue, why don’t they just enforce the Animal Welfare Act? It has always been cruel to keep bitches and puppies in excrement and to not exercise them. And it’s also illegal. If law enforcement (i.e. the RSPCA) is already failing to pursue breeches of this legislation, what use is a breeder code?

A section of page 19 from the report, which illustrates poor living conditions. The top right impact (of a bitch with puppies in a white kennel block) does not seem to indicate any obvious cruelty (though the image quality is poor). Further, it seems the bottom images show sighthound type dogs (black and white dogs pictured), which aren’t typical ‘puppy farm’ dogs. I am skeptical that these images come from a puppy farm. Regardless, all these images are clearly neglectful and inappropriate, and that’s why the Animal Welfare Act doesn’t permit them.

Issues of Criminalising Disadvantaged

When making legislation that makes microchipping and desexing compulsory, little attention is given to those who are disadvantaged financially. We know that most individuals who can afford to microchip and desex their pets do so. Many people who have entire or unidentified animals simply can’t afford the service.

If we create legislation that mandates identification and sterilisation, we run the risk of making criminals out of people who are already highly disadvantaged.

Indeed, we already have issues surrounding dog registration. Dogs in South Australia must be registered by 3 months of age, and councils then enforce this registration, and can issue fines for non compliance. The Committee says:

If the dog is not registered, the return of the animal to its owner will be accompanied by a liability on the owner to pay a fine for permitting the dog to wander at large, another fine for not registering the dog and a further impounding fee. It is very possible that exposure to this sort of cumulative penalty results in some wanted pets not being reclaimed.

This matter-of-fact assessment is presented with no alternative. That is, what’s the alternative? We could remove the section of the Dog and Cat Management Act that allows pets to be held at ransom, or there may be other alternatives. The Committee’s failure to comment in this regard indicates that they seem to consider that pets being held hostage is reasonable. How is that for the benefit of animal welfare?

If we are introducing laws mandating microchipping and desexing, then these services, at the very least, need to be more accessible to people in disadvantaged situations. Subsidised and mobile services would be a great start.

Blaming the Irresponsible Public for Animal Surrenders

The Committee blames people (the ‘irresponsible public’) for making bad choices, saying:

A secondary issue is that there appears to be an unsatisfactory/inappropriate sale of animals in too many cases. The very numbers of dogs and cats abandoned or surrendered to shelters is strong evidence for the failings of animal sourcing. The reasons given(source) for such surrendering make it very clear that many of these animals should never have been purchased in the first place.

The Committee again doesn’t provide appropriate evidence for this assertion. Firstly, that source is wrong. That is, the link provided by the committee is wrong. It doesn’t show reasons for surrendering or relinquishing pets. Indeed, the word ‘surrender’ and ‘relinquish’ don’t appear in the report anywhere, let along on page 12 and 13 (as referenced in the Select Committee report).

Even if reasons for relinquishment were on that report, using a RSPCA annual report to substantiate that ‘reasons given for surrendering’ is flawed. The RSPCA is a charity that keeps pretty good records, but that doesn’t mean that what they produce is research based. In my submission, I provided three researched references that specifically looked at animal relinquishment in my submission – this paper by John et al. and this one from Salman et al., and this one from Marston et al.. Why would the committee choose to look at the RSPCA’s annual report instead of published research?

According to the sources I references, animals are relinquished because their owners are moving, that they feel they can’t care for the pet (sometimes because they’re unwell), because a relationship breaks down, because they have too many pets and council won’t allow them to keep all their pets, or other issues. It’s pretty harsh to suggest that these people “failed” and “should never had… purchased [pets] in the first place”.

What about making rental properties more accessible for pet owners? 15 submissions made this suggestion, but it was not addressed.

Mandatory cooling off periods for pet shop purchased animals was suggested, with shelters and breeders being exempt. The motive is to reduce ‘impulse purchases’, but the downside is that it means that pets have to spend longer in pet shops (an environment not good for puppy development). Is it in the animal’s best welfare to spend an extra two days (or whatever the period may be) in a pet shop? Nope. So why legislate to require animals to spend longer in pet shops?

The logic behind this this, according to the committee, is that a cooling off period “Should result in a decrease in animals surrendered or abandoned, and ultimately in a reduction in euthanasia rates”. There’s a false idea that pets netering shetlers come from pet shops and ‘impulsive purchases’. In reality, most pets entering shelters come from a ‘friend’ or from a shelter (source).

Susan Close then blames the community, the irresponsible public,

But we know that laws can only do so much – how the community treats their animals, and steps up and takes responsibility for de-sexing them, micro-chipping them so they can be found if they are lost, and doesn’t feed unwanted animals they are not taking full responsibility for, will ultimately determine if we are to see the rates of abandoned, abused, dumped and feral dogs and cats decline.

So individual responsibility is the reason animals are put down. Um. I am pretty sure that me and many other pet owners don’t have lethabarb in their homes.

Euthanasia: The public’s fault

The Committee’s report is slathered with anti-community messages, blaming ‘the irresponsible public’ for euthanasia happening in shelters. The report says:

The most recent data from the RSPCA (2011/2012) revealed that the euthanasia rates for dogs and cats in their South Australian shelters were 21% and 54%, respectively. These unacceptable euthanasia rates are the result of several factors, but two of the major causes are a lack of traceability, and unwise purchase of animals

What nonsense!

Animals are being killed in pounds because pounds are killing them.

If a pet can’t be returned home, the next option isn’t to kill them.

If people are being ‘unwise in purchasing animals’, the next option isn’t to kill them.

The assumption is that if a animal is lost or surrendered to a shelter that it must be euthanised. This is not the case. Animals can be rehomed. It’s a revoutionary idea, but pets can actually leave shelters via means other than body bag.

Weak Recommendations for Facilities Killing Pets

We know that the ‘no kill equation‘, and all its associated programs, can reduce shelter killing to less than 10%. There are a number of no kill communities (like those listed on Out the Front Door) that are using the no kill equation to practically eliminate shelter euthanasia. 9 of the submissions received advocated the no kill or ‘getting to zero’ models.

One of the many no kill programs is ‘proactive redemptions’, where shelters and pounds try everything they can to get pets home. This can be listing the pets image online, reviewing lost ads in the paper, having convenient viewing times, and so forth, just to get people to find their pets again and get it out of the facility. We know that the more pets that go home mean less pets that have to be rehomed (or euthanised).

Considering this, it’s upsetting that the Committee made this one small recommendation:

Urge councils to use the “Found Pets” initiative to facilitate the return of dogs to their owners.

While it’s nice to ‘urge’ councils to use the Found Pets initiative, we should really expect and indeed legislate for shelters to make these proactive steps to ensure pets are redeemed. It seems unfair to put legislation on breeders on how they can keep and breed their animals, but then allow councils, shelters and pounds to recklessly kill animals – that is, these facilities have no obligation to find the animal’s past home, or find them a new home, before injecting them with lethabarb.

The Select Committee invited individuals and organisations to comment on issues related to companion animal welfare in section ‘F’, and many chose the opportunity to talk about shelter reform. For example:

- 25 submissions suggested more collection and publication of statistics from councils and shelters,

- 16 submissions thought that ‘big’ and ‘little’ shelters needed to work together,

- 16 submissions advocated trap-neuter-release, and

- 9 submissions advocated for ‘Oreo’s Law’.

Out of these recommendations by the public, not one was addressed, and instead the Committee chose a meek little ‘maybe you’d like to use this app if you want to’ approach. We should be obligating that shelters and pounds do the best for animal welfare through legislation, and not just ‘urge’ them to.

Cat Stuff

This is a dog blog, so I don’t want to go into too much detail regarding the failings of the Select Committee in regard to its recommendations on cat welfare, but here is a quick summarised list:

- The Select Committee seems to advocate WA legislation, which has been significantly criticised by the Saving Pets blog.

- The Committee also seemed to be happy about Mitcham Council’s ‘successful cat registration’ scheme, but that’s not what the Saving Pets Blog calls it… Read more on Mitcham Councils ‘successful’ cat regsitration.

- They seem to adopt a bit of a flawed approach, in that they firstly recognise that “increasing the demands on people who already acknowledge ownership of cats is unlikely to have a significant impact on those that have no owner”, but then go on to suggest cats be registered.

- They want to councils to pay more attention to cat management and be obligated to submit reports about their cat management, but presumably that will just be able killing cats in the council, as no alternatives to trap-and-kill methods were suggested.

Other Stuff

The Committee want every breeder/pet shops/shelter to have a Cert II in Animal Studies. While it doesn’t seem onerous, I worry about the implications on pounds/shelters who are already overstretched with time and resources.

The Committee takes heed of the Dog and Cat Management Board’s stupid “Desex dogs to stop bites” campaign.

The Select Committee quotes the D&CMB saying they want to “shift” the last 33% of entire dogs into desexed dogs, by implementing legislation that makes desexing mandatory. Mandatory desexing is not desirable.

While I don’t object to the Committee wanting all dogs and cats wormed, vaccinated and microchippped before sale, it’s another piece of legislation that is difficult to enforce.

The Good Stuff

I’m happy to give credit to good ideas:

- The Committee supports continued relationships between shelters/rescues and pet shops. An excellent idea.

- The Committee also recommends that breeder details be linked to their microchip (an idea I suggested way back in 2010). So obviously I like this idea too.

It’s disappointing that this is all I got from 64 pages…

In Conclusion

The Committee wants to make microchipping compulsory, which is not bad in itself, but has no suggestions on how this would be enforced nor accompanying legislation on how impounding facilities would be obligated to check chips on incoming animals.

The Committee suggests a breeder licensing scheme despite there being no evidence that such a scheme reduces euthanisa in shelters. Predominately, they want such a scheme to fund the enforcement of new breeder legislation, which is flawed as it practically obligates dogs and puppies to exist in concrete runs.

The Committee ignores the failure of the RSPCA to adequately enforce the Animal Welfare Act.

The Committee ignores the fact that most people cannot afford to microchip and/or desex their pets, and so requiring these steps through legislation would essentially make criminals out of the already disadvantaged.

The Committee calls people who surrender pets to shelters as ‘irresponsible’ despite evidence to the contrary, showing animals relinquished to shelters are often for reasons outside of impulsive buying.

The Committee fails to acknowledge that euthanasia occurs in shelters because shelters euthanise animals, instead attributing blame to external sources.

The Committee does not acknowledge the no-kill philosophies recommended in submissions.

All in all, the Select Committee on Companion Animal Welfare provides no evidence for the recommendations that they make, and overall disregard the submissions made by the public. What a futile process. Hello status quo.

Links of Interest:

See the Hansard.

Microchips appearing in advertisements is legislation in Victoria, but not without problems. Read more: Discussion on DOL.