Where do puppies come from?

First there was Oscar’s Law, who have vilified the pet store trade, calling their producers ‘puppy mills’, and calling for people to adopt animals from shelters and rescues instead.

The RSPCA joined in, with “Close Puppy Factories” and PetRescue with “Where do puppies come from?“.

And the flow on affect was the sin of breeding dogs, with breeders as a whole being criticised, being called ‘greeders’, crucified for any profit they make from puppy sales.

The government had to act, bringing in codes that make dogs ‘Clean and Kennelled‘, which legitimises the practice of keeping dogs on concrete for sanitisation reasons.

And while the production of puppies in puppy farms is objectionable, does it really deserve this much attention?

Where do puppies really come from?

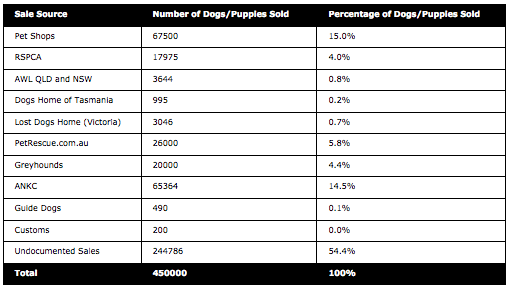

After a lot of research, the best estimate I could get is that there are approximately 450,000 dogs and puppies sold in Australia each year (source: ACAC paper 2009 PDF).

After even more research, I began to see where all these dogs and puppies were coming from. A complete list of sources is at the end of this post, but below is a table showing a breakdown of the numbers.

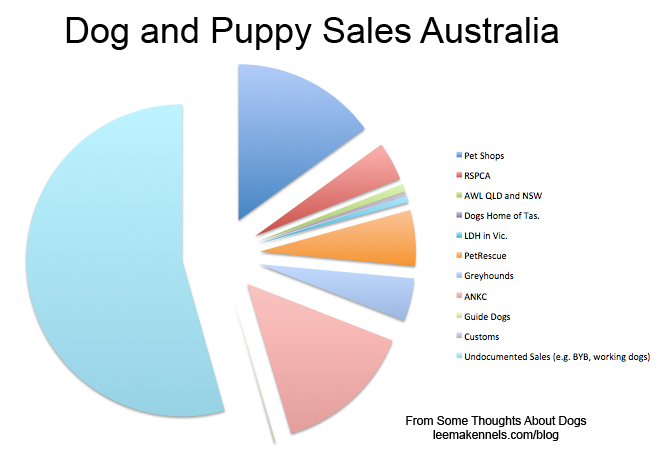

So the question Where do puppies come from? is best answered with We don’t know.

And that’s really case. If the 450,000 number is correct, then we have almost 250,000 dogs a year coming from an unknown source.

Let me put that in a graphic for you:

So who are these unknown breeders of the undocumented sales?

Backyard Breeders

While ‘backyard breeder’ is a generic and undescriptive term, it is probably the most likely producers of the majority of Australian dogs. Backyard breeders are people who occassionally breed (accidentally or deliberately) the dogs they happen to have in the backyard, either motivated by profit or romantic ideals (i.e. “every bitch should have a litter” or “the kids should see the miracle of birth”). These sales are unrecorded. Puppies often go to ‘friends’ or ‘friends of friends’ or they’re advertised in classifieds and given to whoever shows up with a few green bills. These dogs can be of any breed or cross, especially when accidental.

Working Dog Breed

By ‘working dogs’, I mean dogs bred for working stock like cattle or sheep. While there are a few working dog registries, I had trouble finding the actual numbers of registrations (but I’m very happy to be informed!). These dogs are deliberately bred for their herding instincts, and are typically sold to working homes (such as other farmers who need stock dogs). These dogs are typical border collie, kelpie, huntaway or similar types.

Pig Dogs

‘Pig dogs’ are bred for hunting wild boar in Australia, and their ferocity and size are important factors in these breedings. Pig dogs are probably far-less common than the BYB and working dog bred types, and there’s probably some overlap between BYBers and pig dog breeders. These dogs are generally large crossbreeds, commonly large bull breeds crossed with sighthounds or scenthounds.

Camp Dogs

Many of Australia’s indigenous people live on settlements with a number free ranging dogs. Though these dogs are often owned (that is, there is normally a person or a family that identify a number of dogs as ‘theirs’), they are often unconfined and freely breed with one another. Some of these dogs get rehomed through rescue groups like Desert Dogs, and some get desexed on site through groups like AMRRIC. Camp dogs are often smooth-coated dogs with large prick ears, but not always. They are true mixed breeds which do not look like any breed in particular and come in a variety of colours, types, and sizes.

Flaws in the Data

While every attempt has been made to make this analysis as accurate as possible, some of the data used is inevitably flawed.

The figure of 450,000 dogs and puppies sold in Australia annually is an estimate. It is unclear if this is only dogs and puppies sold (so if it does not include ‘give aways’ or dogs that stay in the same home from whelping to death). I have also seen this figure of 450,000 quoted as being just the number of puppies sold in the country annually, and not inclusive of adult dogs. I have used this number in the broadest sense – that it includes puppies and dogs, sold and given away.

The rescue sales are hard to conceptualise. Though many rescues use PetRescue for rehoming, not all do. Those that do don’t necessarily list all animals available on PetRescue. It’s possible that PetRescue data duplicates some of the rehoming by the other rescue groups listed. So, all the rescue stats, from PetRescue and others, are sketchy at best. This especially true considering many groups do not publish their statistics.

While all dogs bred by ANKC breeders out of ANKC dogs must be registered, that doesn’t mean that they all are. The number of dogs bred by ANKC breeders is probably higher (but not much) than that listed.

I tampered with the greyhounds figure a bit. While national registrations are put at about 13,000, we know that many greyhounds aren’t registered. If we work on greyhounds having an average litter size of 6.5, then the figure of 20,000 is a lot more conceivable. (The figure of 13,000 has the average greyhound litter size of 4!)

I just wanted to acknowledge that my data is probably partly inaccurate, but I don’t doubt the overall conclusions I have reached from this data. That is, while some bits may be a little bit off, the whole thing is probably not a lot off.

So what does this mean?

By far the biggest producer of dogs are unknown. We can speculate that they are the backyard breeders, the working dog breeders, the pig dog hunters, or the free ranging dogs on indigenous camps, but without more extensive research we can’t really work out who is our biggest dog-sellers, except that it is likely to be one of these groups.

But it raises the question: If we are concerned about the breeding and sale of dogs in Australia, are registered breeders and pet shops really the people that we need to be going after?

Further reading:

How puppy mills contribute to killing in our pounds (conclusion: they don’t).

The National Animal Interest Alliance produces similar statistics, but for the USA – most puppies come from ‘amateur’ or ‘mixed breed’ breeders.

Why getting pets out of pet shops doesn’t stop puppy farmers

References: Continue reading

I actually think we have pretty good legislation in regard to companion animal welfare. NSW is no exception – they have the

I actually think we have pretty good legislation in regard to companion animal welfare. NSW is no exception – they have the