Socialisation: More is Better

You do not have to read my blog for long to know that I’m a big fan of puppy socialisation. If you read my Puppies 2012 series, you can see the kind of effort I put into puppy raising five years ago (though my methods are different – better – today!).

One of the problems we have with puppy socialisation is that it’s difficult to test the kind of socialisation that works outside of controlled conditions. A recent study used a standardised socialisation program in assistance dogs, and measured the effects. This is a rare opportunity to have a control group for puppy socialisation (as they were all raised in the same conditions in the breeding facility). And the results were fairly impressive!

Study Basis

Undesirable dog behaviours are problematic. Dogs with problem behaviours may be surrendered to rescue. If they occur in specialised breeding programs (like assistance animals, working animals, or sport animals), then dogs that have unsuitable behaviours are the financial burden of wastage. In the worst case scenario, a dog that is aggressive to people or other animals can cause physical and psychological harms.

In many animals, including dogs, we know that juvenile experiences affect development. Puppyhood may be the time to save adult dogs. For dogs, we know that the crucial social development period is 2-13 weeks of age.

Studies on puppies have suggested that early socialisation causes puppies to:

- Mature faster

- Explore more

- Be more resilient

- Perform better on problem-solving task

- Be more successful in training

But there is a paucity in dog research. Many studies only look on the short-term impact on puppy development, and do not look at particular socialisation programs. This study wanted to address this paucity.

Study Design

In this study, an assistance dog puppy-raising facility was used. This meant the puppies could be raised in a controlled way. This study used puppies that were golden retrievers, labrador retrievers, or mixes of.

The control group had fourteen puppies who received the centre’s ‘standard’ socialsiation program.

The study group included nineteen puppies who received the standard socialisation program plus ‘extra’ socialisation 5-7 days a week. This extra program took 5 min per puppy in weeks 1-2, 10 minutes per puppy in weeks 3-4, and 15 minutes per puppy in weeks 5-6.

This socialisation program was tailored to the development of the puppies. For example, there’s no point opening and closing an umbrella around a 10 day old puppy. Basically, the socialisation was specific to that age group’s comprehension, and also layered in a way that meant that it wasn’t overwhelming – just appropriate.

It was also important that the program was effective, quick and easy, and low cost.

Below is the programs that the ‘standard socialisation’ and ‘extra socialisation’ puppies were exposed to. It’s actually a little more complicated than this, as there is specific ages that this stimuli should be experienced by the pups, but I went for this simplified version. You can pursue the full text if you really want to know!

Tactile:

-Puppy picked up

-Puppy stroked gently with fingers

-Handle each puppy in the kennel with bitch

-Groom in kennel

The above is standard. Extra in ES is:

-Wearing velcro collar

-Body touched specifically: head, body, tail, legs, paws

-Holding puppy against: woolen jumper, nylon t-shirt, fleece material

-Stroking puppy with soft towel, rubber glove, soft child’s toothbrush

-Puppy encouraged to move over: carpet, rubber matting, reusable shopping bagAuditory:

-Radio on in the kennel block

-Washing machine sounds

-Plastic bottle with dried pasta inside in kennel with litter

The above is standard. Extra in ES is:

-Sounding near the puppy: a paper bag, a plastic bag, jangling keys, ringing mobile phone, clapping

-Rolling noisy items (e.g. filled toy) in the pen and outside of the penVisual:

-Television on in the kennel block

-Push chair in visual range of kennel

-Charity collection box in visual range of the kennel

The above is standard. Extra in ES is:

-Puppy put in front of TV

-Rolling items in and out of the pen

-Hanging items above the stimulation area

-Opening and closing an umbrella

-A mirror (and encouraging exploration of)Interaction with People:

-Puppy weighed

-Puppy nails clipped

-Puppy carried around block

-Contact with people wearing dress up clothes

-“At least two sessions in a socialisation kennel as a litter”

-Time away from litter

-Grooming on grooming table

The above is standard. Extra ES is:

-Puppy carried around kennel or to socialisation kennel

-Puppy stroked by hand

-Puppy’s teeth and ears examined

-One on one play session for 3 minutes

-Puppy gently restrained for 5-20 seconds

-People wears hat, sun glasses, back packInteraction with Environment:

-Empty plastic bottle in kennel with litter

-Toys in kennel to include: soft, plastic, squeaky, rubber, big soft toy

-At least two session on rubber and grass outside areas (that is at least four sessions outside

-Cardboard box in kennel

-Tunnel in kennel

The above is standard. Extra ES is:

-Experience concrete, grass, and rubber surfaces outside

-Puppy encouraged to climb over an obstacle

-Puppy encouraged to move in and out of door ways

-Gently place a towel over puppy and let it find its way out

Then, at six weeks of age and at eight months of age, the puppies were assessed.

At six weeks, the puppies were exposed to six stimuli, and puppy responses were scored on a seven-point scale. It is most desirable for them to get a score of four – but low scores are least desirable. The same trained staff member assessed all puppies, and did so blind (i.e. did not know which puppy was from which program).

Then, at eight weeks, the puppy’s handler was asked to complete a questionnaire of 40 questions, using a bar scale of 0-100. In this tool, low scores were most desirable, except for the trait of trainability. The puppy handler was also blind (i.e. did not know what program their puppy was from).

Study results

We could simply say: it worked. This small amount of extra socialisation resulted in better dogs, at least until 8 months of age.

“This is the first socialisation program tailored to the developmental stage of puppies from birth to six weeks of age to demonstrate measurable, long-term effects on individual dog behavioural traits.”

At all stages of testing (6 weeks, 8 weeks, and 8 months), the puppies who were on the extra socialisation program did better.

Puppies on the extra socialisation program scored better on:

- Separation related behaviours,

- General anxiety scores,

- Body sensitivity scores, and

- Distraction.

Additionally, extra socialisation puppies showed more desirable attachment, excitability, and animal chase scores (but this was not statistically significant). There was no affect on trainability or energy scores.

On the Puppy Profiling Assessment (where the perfect score is 4), puppies in the standard socialisation program had a mean score of 3.1, while the ones on the extra socialisation program had a mean score of 3.8.

A puppy exposed to things at a young age is likely, as an adult dog, to treat those things as benign. This reduction in novelty logically affects how dogs behave – they are less anxious and distracted by stuff they’ve seen before.

So what should we do?

To quote the article, “The program is recommended for working dog [including assistant dogs], pet dog breeders and shelters.” This really says what we always knew – everyone breeding dogs should be socialising their puppies. This studied showed that what happens before 8 weeks of age affects the puppy throughout at least the first 8 months of life but, presumably, even longer than that.

Ultimately, people are responsible for shaping the experiences of puppies in their care. Arguing that someone ‘doesn’t have time’ to raise puppies well is illogical, according to this study. The puppies on the extra socialisation program did not receive a great deal more time with people, it’s just the way that time was utilised that varied.

For working dogs, early experiences are particularly relevant due to expense and wastage that results from failure in socialisation – and those working dogs raised in kennel environments are at greater risk again.

This study suggests the extra socialisation puppies spent more time away from their littermates which may also result in these bettered scores. Perhaps this time away from their family for small bouts meant they developed better ways of coping with the stress of permanent separation at 8 weeks.

Regardless, we know that socialisation matters, and more is better!

“Mildly stressful early life experience and challenging situations make animals more resilient to stress, less susceptible to emotional disturbances, and promote motor and cognitive skills in adulthood.”

My Thoughts

This study has a relatively small sample – there are only 33 puppies across the two groups. We need to see this study replicated with larger groups in order to make definitive conclusions.

This study has also put a lot of emphasis on appropriate age of exposure. In a clinical or kennel environment, then this formulaic approach to puppy socialisation is understandable. In more naturalistic settings (i.e. home puppy raisers), I don’t think it’s too important to get fussy about what exactly the puppy is getting exposed to at what age, as long as the puppy is not scared and not oblivious to the stimuli.

The big take home point are: socialisation matters, and it can just take 5-15 minutes a day with a puppy to make a difference to the future adult dog.

Further Reading

This study has also been reviewed by:

Giving Puppies Extra Socialization is Beneficial to Them from Psychology Today

Extra Early Socialization for Puppies Makes a Big Difference from Companion Animal Psychology

Source

Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H & Hartmann, A 2017, ‘Improving puppy behaviour using a new standardised socialisation program’, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol 197.

Other Blog Posts

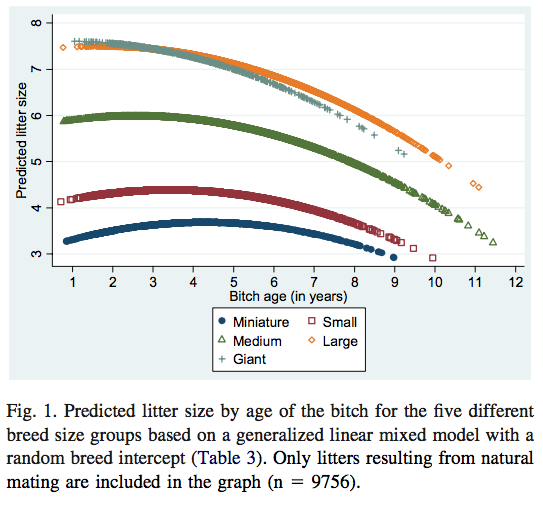

These results are a little different to other studies, which have shown smaller litter sizes as bitches get older. (As in, the results this study got for larger breeds was seen in all breeds in previous studies.) It could be that smaller sample sizes in other studies may have missed this, or that other studies used larger breeds as their data set instead of small or miniature breeds. One suggestion is that small breeds may not mature as quickly as previously believed, and so they’re not able to reproduce until they reach that mark. (To me, this kind of makes sense – considering small breeds often live longer, then it’s likely that they mature more slowly, too.)

These results are a little different to other studies, which have shown smaller litter sizes as bitches get older. (As in, the results this study got for larger breeds was seen in all breeds in previous studies.) It could be that smaller sample sizes in other studies may have missed this, or that other studies used larger breeds as their data set instead of small or miniature breeds. One suggestion is that small breeds may not mature as quickly as previously believed, and so they’re not able to reproduce until they reach that mark. (To me, this kind of makes sense – considering small breeds often live longer, then it’s likely that they mature more slowly, too.)