“Just stop breeding until the pounds are empty”

A increasingly common rhetoric in the rescue community goes along the lines of, “I’m not against breeding, just breeding when the pounds are full” coming along with the suggestion “just stop breeding for a few years, until the pounds are empty”.

This is a misguided suggestion. While this almost sounds good to the uneducated ear, it seems to imply that the dogs in pounds are exactly the type in demand or that there is a dog in a pound to suit every person. Further, ceasing breeding for 3 years would have an impact on not just breeders, but breeds as a whole, on any organisation with working dogs (guide dogs, custom dogs, farm dogs). Also, placing a ban on breeding is just unenforceable. However, the biggest issue with this suggestion is that it doesn’t target the source of the problem. I’ll look at all these issues in more detail.

Pound dogs aren’t for everyone

The dogs available for adoption in pounds is not highly varied. The suggestion that ‘anyone’ can find the dog that is perfect to their household is erroneous. There’s simply not a large variety of dogs in pounds to suit the demand. The reason that breeders (good and bad) are popular is they fulfil a demand that is not met by pounds. Small white fluffies, and indeed small dogs overall, are not well represented in the pound system.

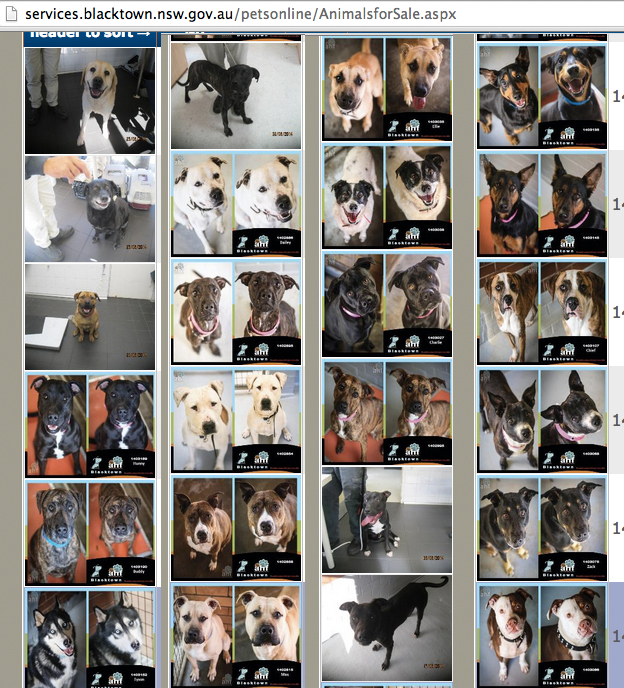

I looked at the first page of dogs available for adoption at Blacktown Pound (NSW). You can see that most dogs are working or bull breed type, and most are medium to large in size. Not a great deal of variety.

Some might argue that if someone really needs or wants a particular type of dog, they should just wait for it to end up in rescue. Is it really fair for someone to wait 2 year or more for a dog that may never appear in rescue? Personally, I was waiting 18 months looking for a dog in rescue (with the requirements that the dog be big, with a wire coat, and very good with other dogs). I gave up waiting and went to a breeder. I feel like I was more than patient, but a dog suiting my needs just wasn’t available to me in this period of time.

On the same date, these are the available pets at Broken Hill Pound NSW available on the 26th of June. Again, the dogs are mostly medium-large working or bull breed types

The other alternative is that people may just get the dog that is available instead of the dog right for them. Did you know that at least two studies (see: one / two) found that 22.5% of the dogs relinquished to a shelter came from a shelter to start with? Being from a shelter is a risk factor for relinquishment in itself, and proposals that people should ‘have to’ acquire a dog from a pound actually seems circular to the end goal of clearing shelters of pets.

Implications for Working Dogs

Seemingly in Australia, about 700 dogs are bred for customs and guide dog work each year. These professions have targeted breeding programs to select for characteristics important for that dog’s individual role. They’ve obviously done the maths, and figure that it’s more cost effective for them to breed their own dogs than take dogs out of shelters and pounds. The proposal that breeders should ‘just stop breeding’ until pounds are empty means that either these programs suffer financially, or the community suffers by not having any dogs at all for several years or more (or forever, really).

Another industry that would suffer would be dogs used on properties for herding or as livestock guardians. These agricultural branches have specially bred dogs for their purposes. Many farms find the work of dogs invaluable, and would also be financially impacted by a breeding ban.

Enforcement is not going to happen

I’ve blogged at length about all the types of legislation that continually goes unenforced Australia-wide, yet touted as ‘good’. In reality, animal legislation is horrendously unenforced. If microchipping laws get flaunted, breeder licensing flops, and the animal welfare acts regularly are violated nation wide, what hope do we have of ceasing dog breeding for a particular period of time?

Dog and Breed Welfare

The idea that breeding should just stop for ‘a few years’ neglects to mention that ‘a few years’ is a long time in a life of a dog.

Let’s say you have a breed that lives until about 12 years old. Three years is a quarter of that dog’s life. That means the dog is middle-aged by the time it is 6 years old.

What I’m getting at is that if you were to ban breeding for a few years, we are going to be breeding older bitches, which we know is riskier. (As bitches age, they have smaller sized litters with bigger individual puppies, which is riskier for the bitch to whelp.)

This means that, for the individual bitches involved, this is bad for their health.

On a broader scope, if breeders choose not to breed their bitches because of a breeding ban, this could put the health of entire breeds in jeopardy. If a bitch is especially important (maybe she has hip scores of 0/0 in a breed with a high incidence of hip dysplasia, or maybe the bitch was imported from Sweden and is important for improving genetic diversity within the breed in Australia), then the loss of this bitch’s progeny to the breed is significant.

Basically, a breeding ban is bad for individual bitches, as they will be bred older, to their detriment. And a breeding ban is bad for breeds, as desirable or important bitches will not be able to make substantial positive impacts on their breed.

Is this really where we should focus?

My biggest gripe with this is it is, again, taking the focus away from the pound – the place where killing happens.

Pounds have an obligation to promote and market their animals. Let’s ban pounds from killing and so obligate them to make changes to their approach!

The other gripe is that this proposal works on the basis that there is an overpopulation program – there isn’t an overpopulation problem.

And: pounds will never be empty! Pounds have an important community service reuniting pets to their families. If my dogs got lost, they’d probably end up in the pound (if not scanned for a chip prior), and I’d be grateful for that.

A ban on breeding, even for a short period, is not a solution to shelter killing.

- Shelters do not have a wide variety of dogs available for adoption, so limiting the availability of some breeds may mean:

- People wait a unreasonably long time to acquire a dog, or

- People acquire a dog unsuitable to their lifestyle (and the dog becomes at greater risk of being relinquished back to the shelter at a later date).

- Working dog breeds (including customs, guide dogs, farm dogs) and the organisations that breed them will suffer, as will the people that these dogs benefit.

- Animal legislation is not enforced and this will be another unenforceable law.

- This proposal is bad for bitches and breed welfare.

- And most importantly, this proposal fails to acknowledge the fault of pounds in the shelter-deaths.

Necessities

Necessities