Aggressive Breeds via Owner Accounts

Establishing ‘aggressive breeds’ without using dog bite data: Using owner reports to establish the most aggressive dog breeds

![]() In 2008, data was published on the ‘most aggressive dogs breeds’, with dachshunds, chihuahuas, and jack russells, coming out on top. Recently, various media reports having been reappearing on my newsfeed on this study, with titles like “The 3 Most Aggressive Breeds Revealed“.

In 2008, data was published on the ‘most aggressive dogs breeds’, with dachshunds, chihuahuas, and jack russells, coming out on top. Recently, various media reports having been reappearing on my newsfeed on this study, with titles like “The 3 Most Aggressive Breeds Revealed“.

Before we begin, please do acknowledge that I adamantly against BSL. I am heavily influenced by research and evidence and, currently, all the evidence points to breed specific legislation never being effective in reducing the incidence of dog bites, in any place globally.

That being said, because I am interested in science, I am interested in studies like this.

So what can this study teach us about aggression in particular dog breeds?

A Jack Russell Terrier: in the top three aggressive breeds according to this study.

The Flaws in Breed Aggression Research

Aggression is a difficult characteristic to assess in dogs. There are a variety of methods that researchers have used, and all have their ‘downsides’.

Using dog bite statistics is not the best course, as most dog bites go unreported, the dog breeds involved cannot be verified and, even if they are verified, it is impossible to understand how many dogs of that paricular breed exist in the community.

If you’re only looking at caseloads from behavioural clinics, then this data is likely to be biased. Generally, people with larger and more dangerous (because of their size) dogs are more likely to seek help, as are people who have dogs aggressive to members of their family. (This article doesn’t mention it, but finances also play a role here – only those owners with the finances to attend behavioural clinics would be represented in such a study.)

There has been some popularity in behavioural tests (cough – D&CMB proposal – cough) where they do threatening or scary things to a dog and score their responses. The problem with this is how this actually relates to the ‘real world’ and the aggression the dog displays in everyday life.

When you ask owners about their dog’s behaviour, their experiences and responses are subjective. And ‘experts’ aren’t much better, with many of them representing ‘shared stereotypes’ whether conclusions from their own experiences.

Study Design

In this particular study, C-BARQ was used. C-BARQ has a good record as being pretty reliable when it comes to asking owners what their dogs are like, temperamentally.

Members of 11 AKC club (‘club sample’) and vet clinic clients (‘online sample’) were invited to partake.

1,553 C-BARQs were completed by the club sample, with 29 excluded as they did not meet criteria.

8,260 C-BARQs were completed by the online sample, with 1,257 excluded for being mixed breeds or with no breed indicated, and 2,051 excluded as there was less than 45 of that breed represented – so in the end the sample was 4,952 responses for 33 different breeds.

They were rated on aggression towards strangers, owners, and other dogs.

Summarised Findings

The online sample and breed club sample differed in some ways. Breed clubs submitted more intact dogs, more female dogs, and older dogs than those in the online sample. Despite this, the results were quite consistent across the two samples.

Dog aggression was the most common and most severe type of aggression in the study, but dog aggression was not correlated with aggression to people. This supports the widely held view that ‘dog aggression’ does not indicate a risk to people. Similarly, aggression towards household-dogs was not associated with aggression towards other dogs or people. From the data in this study, more than 20% of Akitas, Jack Russell Terriers, and Pit Bulls had serious aggression towards unfamiliar dogs.

When it came to aggression towards people, the highest rates were found in smaller breeds, ‘presumably’ because aggression from smaller (and so more manageable and less dangerous) dogs is more tolerable.

When it came to aggression towards owners, more than half of the aggressive displays towards owners were associated with the owner taking food or something else away from the dog.

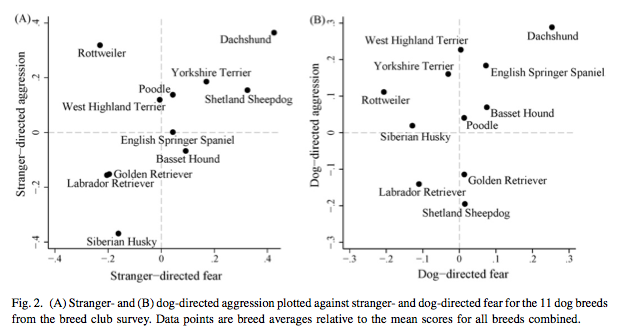

While fear in animals is associated with aggression, fear was not strongly correlated with aggression in this study. Some dogs were aggressive but not fearful, some were fearful but not aggressive, and some were fearful and aggressive.

A quote from the study on their findings,

“Although some breeds appeared to be aggressive in most contexts (e.g., Dachshunds, Chihuahuas and Jack Russell Terriers), others were more specific. Aggression in Akitas, Siberian Huskies, and Pit Bull Terriers, for instance, were primarily directed toward unfamiliar dogs. These findings suggest that aggression in dogs may be relatively target specific, and that independent mechanisms may mediate the expression of different forms of aggression.”

Further results on a more breed-by-breed basis (breeds listed alphabetically):

- Akitas rated higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- American Cocker Spaniels rated higher for aggression towards their owners than other breeds.

- Australian Cattle Dogs rated higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds, and also rater higher for aggression towards strangers.

- Basset Hounds rated higher for aggression towards their owners than other breeds, but were below average when it came to stranger directed aggression.

- Beagles rated higher for aggression towards their owners than other breeds.

- Bernese Mountain Dogs were among the breeds least aggressive towards people and dogs, and ranked below average on stranger directed aggression.

- Boxers rated higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- Brittanys were among the breeds least aggressive towards people and dogs, and ranked below average on stranger directed aggression.

- Chihuahuas rated higher for aggression towards people (both owners and strangers) and higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- Dachshunds rated higher for aggression towards people (both owners and strangers) and higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- English Springer Spaniels rated higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds, and also rated higher for aggression towards owners. Showed bred English Springer Spaniels were more aggressive than field bred lines.

- German Shepherd Dogs rated higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- Golden Retrievers were among the breeds least aggressive towards people and dogs, and ranked below average on stranger directed aggression.

- Greyhounds were among the breeds least aggressive towards people and dogs, and ranked below average on stranger directed aggression.

- Jack Russell Terriers rated higher for aggression towards people (both owners and strangers) than other breeds and higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- Labrador Retrievers were among the breeds least aggressive towards people and dogs, and ranked below average on stranger directed aggression. Field bred labradors were more aggressive than show bred labradors.

- Pit Bulls rated higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- Siberian Huskies ranked below average on stranger directed aggression.

- West Highland White Terriers rated higher for aggression towards other dogs than other breeds.

- Whippets were among the breeds least aggressive towards people and dogs, and ranked below average on stranger directed aggression.

Warning against reaching conclusions on the genetic basis of aggression…

The authors caution, “Demographic and environmental risk factors for the development of canine aggression need to be investigated across a variety of breeds so that both generalized and breed-specific influences can be identified.”

So what do you think? Are these studies results consistent with your experiences?

Reference:

Deborah L. Duffy, Yuying Hsu, & James A. Serpell (2008). Breed differences in canine aggression Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 114 (3), 441-460 DOI: 10.1016/j.applanim.2008.04.006

Further Reading

More on C-BARQ: Can breeders breed better?